Author:

Nurzali Ismail, School of Communication, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Research Consultant for the Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (PCVE) at International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation (ISTAC-IIUM)

“I will carry out and [sic] attack against the invaders, and will even live stream the attack via Facebook” – The Christchurch terror attacker on 8Chan message board, shortly before executing his act of terror.

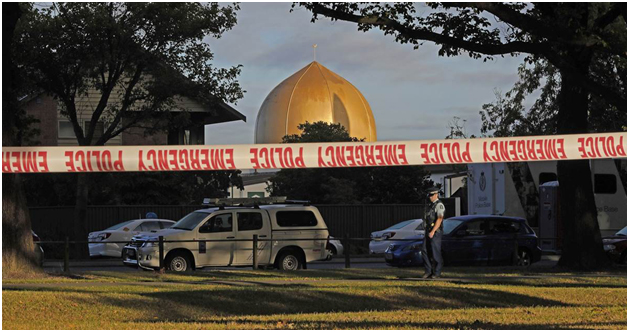

It has been over a year since the terrifying Christchurch mosque shootings. The incidents that took place at Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Mosque during the Friday prayer claimed 51 innocent lives (Ismail, 2020). The offender, believed to be a white supremacist, was arrested shortly after executing his attacks. A year on, he was found guilty and sentenced to life without parole (Stoakes, 2020). The high court decision to give a very severe sentence to the offender brought relief to the society after a long grief due to the tragedy.

Two consecutive mass shootings occurred at mosques in a terrorist attack in Christchurch, New Zealand, during Friday Prayer on 15 March 2019.

It is no doubt that the Christchurch terror attacks have changed many facets of life. Right now, there is no place in the world that can be claimed to be safe from terror. Even New Zealand, a country that is often regarded a safe haven, now has to deal with the aftermath of the attacks by providing measures to counter the threat of terrorism. The incidents, according to the Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, have fundamentally changed the nation (BBC, 2020).

New Zealand PR Jacinda Ardern hugs a mosque-goer at the Kilbirnie Mosque after the nation’s worst terrorist attack (Photo: Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

Some argue that new media was partly to be blamed for what happened in Christchurch (Bogle, 2019; Murrell, 2019). The fact that video footages of the shooting massacres were spread and viral on the internet triggered outrage among the public (Wakefield, 2019). The offender’s usage of live streaming function on social media to execute his act of terror also has prompted calls for technology companies such as Google and Facebook to change the way how their platforms work. They were urged to play a more proactive role in countering terrorism and violent extremism (Stewart, 2019).

The offender’s usage of internet forums and social media in relation to the attacks indicate how new media can be wrongly used to carry out terror. It is important to note that, with the advancement of new media technologies and increased connectivity, terrorism and violent extremism can easily spread to mass audience all over the world (Bender, 2019).

While it is easy to associate new media with risks related to terrorism and violent extremism, the reality is more complex than it seems. After all, we should be careful not to fall into the trap of simplistically establishing relationship between new media, terrorism and violent extremism without empirical evidences. Such mistake would make effort to counter terrorism and violent extremism more difficult. Hence, this article aims to provide a better understanding of new media, its nature and how it relates to the process of radicalization, violent and extremism. Based on the existing literature, the author also offers ways how to move forward in regard to new media, terrorism and violent extremism.

New media and the creation of the global village

New media has changed the way we live. It is essential in every aspect of our lives including communication, socialization, commerce, education and entertainment. Considering the situation that we currently live in and our dependency on new media, it is difficult to imagine living without technologies such as smartphones, computers and tablets or to remain productive without being connected to the internet.

The term new media is often subjected to debate and confusion due to it being loosely defined. One of the arguments that is often raised is, every media is considered new at the beginning and would eventually become old. For instance, books, newspapers, cinema, radio and television were once, considered new innovations that were influential and brought significant societal changes during their time of inventions.

Each social media platform acts as a digital home for individuals, allowing people to express themselves through the global village.

In response to the debate over the term new media and what should constitute ‘new’ and ‘old’ media, Creeber and Martin (2009) explained that, new media should be associated with changes brought by the digital communication technologies. The important characteristics of new media include being digital, interactive, hyper-textual, virtual, networked and simulated (Lister, Dovey, Giddings, Grant & Kelly, 2009). Flew (2008) added, new media is made of the combination of three Cs, which are computing and information technology, communication networks and digitalized media and information content. New media arises from the process of convergence where different forms of digital media technologies are linked and simultaneously used together (Flew, 2008; Ismail, 2014).

The impact of new media on society is enormous. Social media for instance, has transformed from being a medium to socialize and maintain relationship to a powerful tool for communication, news sharing and consumption, commerce and many other integral aspects of our everyday life. The increased in connectivity and communication that new media generates, has without doubt, brought into our lives the global village, a concept coined by Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s.

According to McLuhan (1967), as connectivity increases, everything else is changing, particularly the structure and pattern of social interdependence. While McLuhan’s global village proposition may actually influenced by the transformation brought by the electronic media such as radio and television in the 1960s (Georgiadou, 2002), it paves the way to our understanding of how people all across the globe are connected through the use of new media communication technologies.

Besides communication, another distinctive feature of the global village is the opportunity for everyone to become content creator and information producer. This, is evidenced in the way how news and information are posted and shared through social media platforms. While this is a good thing as we now have information at our fingertips, it also present risks associated to misinformation and false news.

Living in the global village, we are dealing with information overload. News travels fast, but its accuracy is often call into question (Karlsson, 2011; Renjith, 2017). Gone are the days where the authority or news organization has absolute control over the flow of information. For instance, in the event of an emergency, unverified news and information spread faster on the social media sphere compared to the official reports that are provided by the authority (Alejandro, 2010). Even though many are aware of the possibility of inaccurate social media information (Ismail, Ahmad, Noor & Saw, 2019), they are still tempted to consume it due to motivation related to the fulfillment of information needs, desire for insider information and immediacy (Austin, 2012; Ismail et al., 2019).

In relation to terrorism and violent extremism, the connectivity afforded by new media presents an unprecedented challenge to the authority, something that has never been experienced before. The complex process of radicalization and violent extremism that take place online requires the authority to quickly adapt to the situation and to be able to provide effective counter strategy.

New media as weapon

Modern warfare is a high-tech battlefield where social media has emerged as a surprising — and effective — weapon.

In their book entitled Like War: The Weaponization of Social Media, Singer and Brooking (2018) argued that, social media is fast becoming a lethal tool. It was claimed that social media was used to hack and leak documents, as well as to influence public perception during the 2016 United States Presidential Election (Strohm, 2016; Singer & Brooking, 2018). It was also reported that social media is widely used by terrorist groups as a powerful tool for radicalization, recruitment and propaganda (Singer & Brooking, 2018).

Unlike during the late 1990s and the early 2000s period where social media was mainly used as a mean for communication as well as for building and maintaining relationships, its usage today has significantly transformed. In this present time, social media is regarded as a persuasive communication medium that is capable of influencing people’s beliefs and behaviors. Similar to the way how people are influenced to purchase a certain product after being exposed with advertisements on social media, they can also be influenced through exposure with other kinds of messages including propaganda.

The advancement of new media technologies have made propaganda and deceptive communication tactics possible including through the use of social bots or the automated social media accounts. According to Farkas and Neumayer (2020):

With the evolution of digital technologies and platforms, communication strategies have developed concurrently, as political actors have iteratively sought to increase their influence…With the development of digital platforms from websites to social media environments, new modes of propaganda have emerged (p. 708).

While social bots can be very effectively used to communicate with human beings, particularly in carrying out task as a customer service representative of the organization on social media, its usage is also often associated with fake news and manipulations.

Using media technology to propagate ideology is not a new thing. Mass media like film, radio, television and newspapers have long been used as tools to communicate messages for the purpose of persuasion and propaganda. Hitler’s exploitation of films to influence the beliefs of the Germans and to garner support for the Nazi (Jason, 2013) and the media reporting of the Iraq War in 2003 (Kellner, 2004), are instances of how propaganda through the mass media works.

The main differences between social media and the conventional media like film, radio, television and newspapers are in term of ownership, control and conversation that they generate. While the conventional media is generally very expensive and are owned by conglomerates, social media can be owned by anyone. Social media also presents an opportunity for users to publish content freely and share it with anyone across the platform.

It should also be noted that the conventional media reaches larger audience, but it only capable of providing one-way communication flow. On the contrary, social media audience is more targeted, offer more control and provide avenue for two-way communication to take place. The way how social media works, gives rise to a more personalized communication, where the power of persuasion is essential. A social media message that is persuasive, has the potential to influence the target audience, hence affecting their beliefs, attitudes and behaviors.

According to Fuchs (2018), even though the media landscape has significantly transformed, the propaganda model as coined by Herman and Chomsky over three decades ago remains relevant to date. All the ingredients of the propaganda model that comprise of (a) size, ownership and profit orientation, (b) advertising, (c) sourcing, (d) mediated lobbying and (e) ideologies can be utilized in the study of new media (Fuchs, 2018). It provides a useful lens to analyze propaganda in the age of new media (Fuchs, 2018). This, if it is critically done by taking into consideration of subjects, processes, objects, contradictions, economy, politics and culture, as proposed by Fuchs (2018), can help to further understand the impact of exposure to propaganda messages online and its relationship with the process of radicalization.

Understanding extremists’ narratives online

As discussed in the previous section, the liberated nature of new media is generally a good thing, but it can also be exploited, turning it to be a lethal weapon of destruction. This is evidenced in the rise of disinformation and propaganda on the online sphere. In regard to violent extremism, it was reported that, new media is a breeding ground for radicalization as it provides increased opportunity for people to socialize, to be exposed to online messages and to strengthen their existing beliefs (Von Behr, Reding, Edwards & Gribbon, 2013). It should be understood though, that new media helps to facilitate the radicalization process, and not driving it, as assumed by many (Behr et al., 2013).

Earlier studies have indicated that there are numerous ways used by the extremists to radicalize individuals using new media (Thompson, 2012; Gill et al., 2017; Ganesh & Bright, 2020). According to Gill et al., (2017):

The Internet is largely a facilitative tool that affords greater opportunities for violent radicalization and attack planning. Nevertheless, radicalization and attack planning are not dependent on the Internet and researchers need to look at behaviors, intentions, and capabilities. Offenders hampered by their co-offending environment or the ambitions of their plot are afforded opportunities online (p. 113).

It is also important to note that, the way how new media is used by the extremists differs in term of online knowledge and sophistication, and it is also largely influenced by extremists’ ideology, strategy and communication (Gill et al., 2017). However, new media should not be simplistically regarded as a substitute for offline radicalization because both are used to serve different purposes, as well as, to complement each other (Gill et al., 2017).

While the importance of new media for the extremists is widely known due to its ability to provide command, control and communication (Thompson, 2012), greater understanding on the narratives and messaging aspect is necessary (Archetti, 2015). However, due to limited number of studies that are focusing on the extremists’ strategic communication aspect of new media (Archetti, 2015), a question emerges; what kind of narratives that are used online to radicalize individuals?

According to Van Ginkel (2015), the extremists are good at exploiting the new media and this is evidenced through their narratives and the craft of effective messages online. Using the Jihadi-Salafi Movement as example, Van Eerten, Doosje, Konijn, de Graaf and Goede (2017) elaborated that, its narratives online are mainly based on (a) highlighting grievances – mainly by putting blame on the West, (b) promising a better world and vision through the Islamic Caliphate political system and, (c) providing solution to the existing problems and injustices through violent Jihad. Van Eerten et al., (2017) added, the Jihadi-Salafi Movement effectively uses various social media platforms such as YouTube to serve propaganda and psychological functions, Facebook for social networking and recruitment purposes and Twitter as a medium to reach large audience.

In comparison to the Jihadi-Salafi Movement, the far-right groups are using justifications related to the threats of insecurity and extinction as part of their narratives, which justify the need for violence as a form of self-defense (Marcks & Pawelz, 2020). In a separate study carried out by Sterkenburg, Smit and Meines (2019), it was explained that, the far-right groups are making use of issues related to the struggle of identity, masculinity, victimhood due to policies that are favoring the minorities, perceived loss of government sovereignty and eco-fascism as their narratives online.

Differences in narratives employed by the extremists is only one of many considerations that have to be taken into account when trying to understand the radicalization process online. For instance, as argued by Archetti (2015), being exposed to the extremists’ online media materials does not necessarily make any individual to become radicalized. Here, it should be noted that, new media is dynamic, continuously evolving and very complex (Guliciuc, 2014). Hence, any attempt to unravel radicalization process online need to be based on thorough understanding of new media and communication.

Moving forward

One of the most notable approaches for countering terrorism and violent extremism is by providing counter narratives on new media (insert citation). However, Ferguson (2016) argued that the effectiveness of such approach is unproven. This is mainly due to the lack of knowledge in the area. Lee (2020) added, the main problem with providing counter narratives online is that, many of these messages are too formal, which make them become less convincing. Hence, if counter narratives are to work, it is necessary to also consider informal content and the possibility for collaboration between formal and informal actors (Lee, 2020). Alternatively, it is also proposed that, instead of focusing only on countering extremists’ narratives, a message strategy is used by focusing on central issues related to identity, reconciliation and tolerance (Ferguson, 2016).

Even though the impact of counter narratives approach is questioned, there is no doubt, that in some ways, it has managed to disrupt terrorism and violent extremism propaganda messages online (Reed & Ingram, 2019). However, due to the reactive nature of disruption, redirection and providing counter narratives approaches, Reed and Ingram (2019) suggested that, effort to curb terrorism and violent extremism should employ proactive approaches that are built upon strong engagement with the target audience.

Strong engagement with target audience can be built through strategic communication which focuses on tactics and strategies that revolve around campaign and message design (Reed, Ingram & Whittaker, 2017). Based on the “Linkage-Based” two-tiered framework, Ingram (2016) proposed that, it is important to challenge the extremists’ system of meaning or perceived belief and to provide alternative narratives to the target audience. The message design aspect comprises of (a) pragmatic and identity-choice messaging, (b) offensive and defensive messaging and (c) the leveraging process (Ingram, 2016). The same framework also identifies the key themes that are either positive messaging or negative messaging (Whittaker & Elsayed, 2019). They should be consistently communicated throughout the campaign (Whittaker & Elsayed, 2019).

In addition, engagement with the target audience can also be performed through community related events and activities (RAN, 2019). According to Mitts (2019), community engagement initiatives are effective in suppressing online extremists’ expression, and this is evidenced in the significant decreased of pro-ISIS content on social media. In order to be successful, community based engagement efforts need to address issues related to building trust, setting priorities, choosing partners, consultations and input (Cherney & Hartley, 2017).

The complexity of the issue, context, as well as, the lack of conceptualization and theoretical underpinning continue to hamper effort to counter terrorism and violent extremism (Nasser-Eddine, Garnham, Agostino & Caluya, 2011; Hardy, 2018). One of the challenges is that, many of the earlier initiatives were planned and executed either based on old and irrelevant theories, or with new, but untested approaches (Schomerus, El Taraboulsi-McCarthy & Sandhar, 2017). The new media environment which is dynamic and constantly changing require a thorough understanding of the issue, context and the way how countering terrorism and violent extremism initiatives should be planned and executed.

Despite the advancement of new media and the way how the online platforms are being exploited, it is important to note that the acts of terrorism and violent extremism take place through both online and offline spheres. Here, ‘online’ and ‘offline’ spaces are not distinct, hence, they should not be studied separately (Lehane, 2018). More studies in this area is necessary, especially within a specific context, as knowledge and practices with regard to countering terrorism and violent extremism are still developing. Local knowledge and practices are necessary as every context differs to the other (Holmer, Bauman & Aryaeinejad, 2018).

References

Alejandro, J. (2010). Journalism in the age of social media. Retrieved from University of Oxford.

Archetti, C. (2015). Terrorism, communication and new media: Explaining radicalization in the digital age. Perspectives on terrorism, 9 (1).

Austin, L., Liu, B., & Jin, Y. (2012). How audiences seek out crisis information: Exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of applied communication research, 40(2), 188-207.

BBC (2020). Christchurch mosque attacks: NZ has ‘fundamentally changed’ says PM. BBC. world-asia-51850210

Bender, S. M. (2019). Social media create a spectacle society that makes it easier for terrorists to achieve notoriety. The Conversation.

Bogle, A. (2019). Social media deserves blame for spreading the Christchurch video, but so do we. ABC News.

Cherney, A., & Hartley, J. (2017). Community engagement to tackle terrorism and violent extremism: Challenges, tensions and pitfalls. Policing and society, 27 (7), 750-763.

Creeber, G., & Martin, R. (2009). Introduction. In G. Creeber & R. Martin (Eds.), Digital cultures (pp. 1-10). Berkshire: Open University Press.

Farkas, J. & Neumayer, C. (2020). Disguised propaganda from digital to social media. In Hunsinger J., Allen M., Klastrup L. (Eds.), Second international handbook of internet research. Springer, Dordrecht.

Ferguson, K. (2016). Countering violent extremism through media and communication strategies: A review of the evidence. Partnership for Conflict, Crime & Security Research (PaCCS).

Flew, T. (2008). New media: An introduction (3rd ed.). South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University press.

Fuchs, C. (2018). Propaganda 2.0: Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model in the age of the internet, big data and social media. In: Pedro-Carañana, J., Broudy, D. and Klaehn, J. (eds.). The propaganda model today: Filtering perception and awareness. Pp. 71–92. London: University of Westminster Press.

Ganesh, B., & Bright, J. (2020). Countering extremists on social media: Challenges for strategic communication and content moderation. Policy & internet, 12 (1), 6-19.

Georgiadou, E. (2002). McLuhan’s global village and the internet. 1st International Conference on Typography & Visual Communication.

Gill, P., Corner, E., Conway, M., Thornton, A., Bloom, M., & Horgan, J., (2017). Terrorist use of the internet by the numbers: Quantifying behaviors, patterns, and processes. Criminology & public policy, 16 (1), 99-117.

Guliciuc, V. (2014). Complexity and social media. Procedia – social and behavioral sciences, (149) 2014, 371-375.

Hardy, K. (2018). Comparing theories of radicalisation with countering violent extremism policy. Journal for deradicalization. 15, 76-110.

Holmer, G., Bauman, P., & Aryaeinejad, K. (2018). Measuring up: Evaluating the impact of P/CVE programs. United States Institute of Peace.

Ingram, H. J. (2016). A “Linkage-Based” approach to combating militant Islamist propaganda: A two-tiered framework for practitioners. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT).

Ismail, N. (2014). Young people’s use of new media through communities of practice. Monash University Australia.

Ismail, N., Ahmad, J., Noor, S.M., & Saw, J. (2019). Malaysian youth, social media following, and natural disasters: What matters most to them? Media watch, 10 (3), 508-521.

Ismail, N. (2020). Heightened risk of violent extremism. The Star.

Jason, G. (2013). Film and propaganda: the lessons of the Nazi film industry. Reason Papers, 35(1), 203+.

Karlsson, M. (2011). The immediacy of online news, the visibility of journalistic processes and a restructuring of journalistic authority. Journalism, 12 (3), 279-295.

Kellner, D. (2004). Media propaganda and spectacle in the war on Iraq: A critique of U.S. broadcasting networks. Critical studies critical methodologies, 4 (3), 329-338.

Lehane, O. (2018). Dealing with frustration: A grounded theory study of CVE practitioners. International journal of conflict and violence, 12, 1-9.

Lee, B. (2020). Countering violent extremism online: The experiences of informal counter messaging actors. Policy & internet, 12 (1), 66-87.

Lister, M., Dovey, J., Giddings, S., Grant, I., & Kelly, K. (2009). New media: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Oxon: Routledge.

Marcks, H., & Pawelz, J. (2020). From myths of victimhood to fantasies of violence: How far-right narratives of imperilment work. Terrorism and political violence, 32, 1-18.

McLuhan, M. 1967. The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. London: Penguin Press.

Mitts, T. (2019). Countering violent extremism and radical rhetoric. Columbia University.

Murrell, C. (2019). The Christchurch shooting was streamed live, but think twice about watching it. ABC News.

Nasser-Eddine, M., Garnham, B., Agostino, K., & Caluya, G. (2011). Countering violent extremism (CVE) literature review. Department of Defence, Australian Government.

RAN (2019). Preventing radicalization to terrorism and violent extremism: Community engagement and empowerment. Radicalisation Awareness Network.

Reed, A. G., & Ingram, H. J. (2019). A practical guide to the first rule of CTCVE messaging: Do violent extremists no favours. Europol Public Information.

Reed, A. G., Ingram, H. J., & Whittaker, J. (2017). Countering terrorist narratives. Policy Department for Citizen’s Rights and Constitutional Affairs. European Union.

Renjith, R. (2017). The effect of information overload in digital media news content. Communication and media studies, 6 (1), 73-85.

Schomerus, M., El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, S., & Sandhar, J. (2017). Countering violent extremism (Topic guide). Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Singer, P. W. & Brooking, E. T. (2018). Like war: The weaponization of social media. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Sterkenburg, N., Smit, Q., & Meines, M. (2019). Current and future narratives and strategies of far-right and Islamist extremism. RAN Centre of Excellence.

Stewart, A. (2019). Social media companies grapple with how to moderate content in wake of Christchurch attacks. The National News.

Stoakes, E. (2020). New Zealand’s grief turns to joy as mosque shooter Brenton Tarrant is sentenced to life in prison. The Washington Post.

Strohm, C. (2016). Russia weaponized social media in U.S. Election, FireEye says. Bloomberg.

Thompson, R. L. (2012). Radicalization and the use of social media. Journal of strategic security, 4 (4), 167-190.

Van Eerten, J-J., Doosje, B., Konijn, E., Graaf, B. D., & Goede, M. D. (2017). Developing a social media response to radicalization: The role of counter-narratives in prevention or radicalization and de-radicalization. University of Amsterdam.

Van Ginkel, B. T. (2015). Responding to cyber jihad: Towards an effective counter narrative. The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

Von Behr, I., Reding, A., Edwards, C. & Gribbon, L. (2013). Radicalisation in the digital era: The use of the internet in 15 cases of terrorism and extremism. RAND Europe.

Wakefield, J. (2019). Christchurch shootings: Social media races to stop attack footage. BBC.

Whittaker, J., & Elsayed, L. (2019). Linkages as a lens: An exploration of strategic communications in P/CVE. Journal for deradicalization, 20, 1-46.

Users Today : 0

Users Today : 0 Total views : 8430

Total views : 8430

Recent Comments